ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of energy. Join Dispatches, a publication that spotlights wrongdoing across the nation, to obtain our tales in your inbox each week.

Reporting Highlights

Damaged Guarantees: A Trump administration freeze of funds designated to assist new refugees is inflicting chaos for households and forcing nonprofits to chop promised companies.

Annoyed Households: Immigrants receiving much less assist from caseworkers are struggling to seek out work and navigate well being care programs.

Overwhelmed Volunteers: Church members and different volunteers are filling some gaps, however they don’t have the identical sources as the help companies that used to do that work.

These highlights had been written by the reporters and editors who labored on this story.

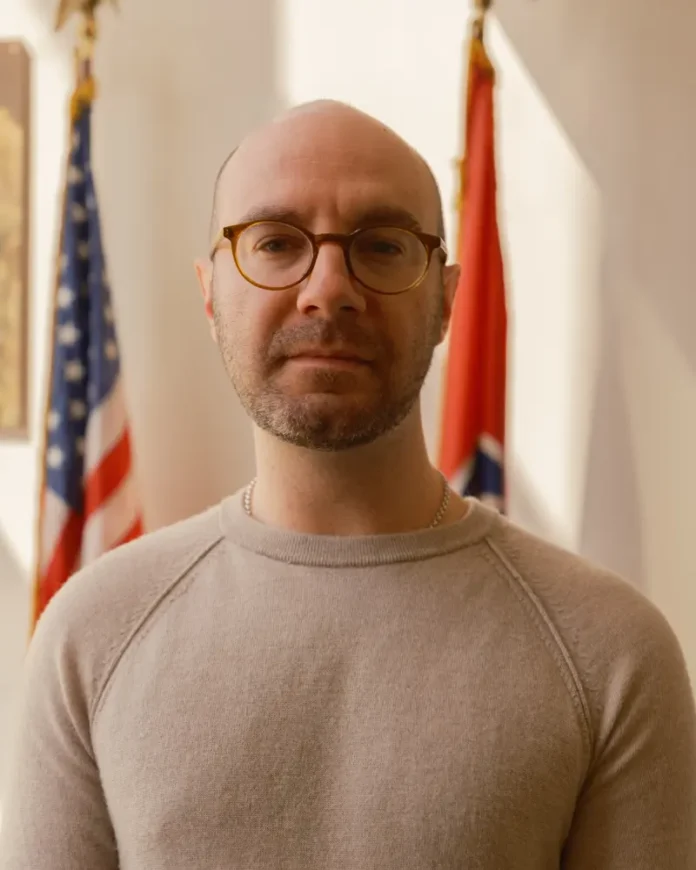

When Max Rykov began studying a Jan. 24 letter despatched to the leaders of the nation’s 10 refugee resettlement companies, he discovered the wording imprecise however ominous. The companies had been ordered to “cease all work” funded by the Division of State and “not incur any new prices.”

At first, he puzzled if the order from the Trump administration was solely focusing on refugee work in different nations. Rykov, then the director of improvement and communications at a refugee resettlement accomplice in Nashville, started texting colleagues at different companies. “What does it imply?” he requested.

By Monday, three days after the memo, it grew to become clear. The Nashville Worldwide Middle for Empowerment, together with related nonprofits throughout the nation, wouldn’t have entry to the cash the federal government had promised to refugees for his or her first three months in america. That day, NICE laid off 12 of its 56 resettlement employees members and scrambled to liberate funds to pay for the fundamental wants of almost 170 folks depending on the frozen grants.

Max Rykov arrived within the U.S. as a toddler and went on to turn out to be the director of improvement and communications on the Nashville Worldwide Middle for Empowerment, which helps refugees resettle.

Credit score:

Arielle Weenonia Grey for ProPublica

Rykov knew precisely what was at stake, and that delivered a further dose of dread. Born within the former USSR, he and his household arrived within the U.S. as refugees in 1993, fleeing the collapse of the Soviet Union, the financial devastation and discrimination in opposition to Soviet Jews. He was 4 years outdated, and it was bewildering. Although his household was a part of one of many largest waves of refugee resettlement in U.S. historical past, they ended up in a spot with few Russian immigrants.

Life in Birmingham, Alabama, a post-industrial metropolis formed by the Civil Rights motion and white flight, revolved round Saturday school soccer video games and Sunday church. Rykov stated his household felt “barren” within the U.S. away from their tradition. Birmingham’s Jewish group was small and the Russian inhabitants tiny.

However a neighborhood Jewish group sponsored the Rykovs and paired them with a “friendship household.” The group rented them an residence and furnished it. Then the group helped Rykov’s mother and father discover work. And Birmingham’s Jewish group banded collectively to fund scholarships for Rykov and different Soviet refugee youngsters to attend a non-public Jewish faculty, the place Rykov felt much less remoted.

He went on to attend the College of Alabama and overcame his feeling of otherness. After commencement, he discovered objective in bringing folks collectively via his work organizing cultural occasions, together with arts festivals and an grownup spelling bee, doing social media outreach for the Birmingham mayor and, in 2021, discovering a dream job at a Nashville nonprofit dedicated to the very efforts that he believes helped outline him.

When Rykov heard that President Donald Trump’s second administration had ordered cuts to the refugee program, his ideas raced to the Venezuelan refugee household his group was helping, an older girl ill, her daughter who cared for her and the daughter’s two youngsters, one not but kindergarten age. None of them spoke English, and there was no plan for a way they’d cowl the hire, which was due in 4 days.

“It is a promise that we made to those folks that we have now reneged on,” he stated. “Is that basically what’s occurring? Yeah, that’s precisely what’s occurring.”

As the belief of what lay forward set in, Rykov began to cry.

Over the following two months, the Trump administration carried out and defended its destabilizing cuts to the refugee program. The strikes introduced wave after wave of uncertainty and chaos to the lives of refugees and people who work to assist resettle them.

One of many largest nonprofit companies that perform this work, the U.S. Convention of Catholic Bishops, laid off a 3rd of its employees in February and stated Monday that it might finish all of its refugee efforts with the federal authorities. A Jewish resettlement group, HIAS, lower 40% of its staff. Because the teams battle authorized battles to recoup the hundreds of thousands of {dollars} the federal government owes them, some have been pressured to shut resettlement places of work fully.

The Nashville Worldwide Middle for Empowerment remains to be struggling to maintain its personal afloat. Though NICE employees members had anticipated some cuts to refugee packages underneath Trump, they stated they had been caught off guard when reimbursements for cash already spent failed to look and by the dwindling alternatives to hunt recourse.

After a choose ordered the Trump administration to restart refugee admissions, the administration responded by canceling contracts with present resettlement companies and saying plans to seek out new companions. And the administration has indicated it would stay resistant, refusing to spend hundreds of thousands appropriated by Congress for refugees.

“Many have misplaced religion and belief within the American system due to this,” stated Wooksoo Kim, director of the Immigrant and Refugee Analysis Institute on the College of Buffalo. “For a lot of refugees, it could begin to really feel prefer it’s no completely different from the place they got here from.”

In court docket paperwork, legal professionals for the Division of Justice argued the U.S. doesn’t have the capability to help massive numbers of refugees.

“The President lawfully exercised his authority to droop the admission of refugees pending a dedication that ‘additional entry into america of refugees aligns with the pursuits of america,’” the movement stated.

In Nashville, that anxiousness has been taking part in out week after week in tear-filled places of work and in residence complexes teeming with households who fled struggle and oppression.

Rykov couldn’t assist however really feel overwhelmed by the intense shift in attitudes about immigrants in only a few years. In 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, his household’s dormant fears about Russia had been reawakened — however they felt a surge of pleasure for the U.S. when it stepped as much as assist Ukraine and welcome its refugees.

Months after the invasion, Ukrainian athletes got here to Birmingham for the World Video games, which has similarities to the Olympics. Once they entered the stadium waving the Ukrainian flag, the gang gave them a standing ovation. His mother and father, who’d by no means felt fairly at residence within the U.S., loudly joined within the “U-S-A” chant that adopted.

However now, three years later, was all of America now able to abandon refugees? Rykov was beginning to see the indicators, however he refused to consider it and as an alternative recommitted himself to the work.

He and his colleagues reached out to each donor of their community and referred to as a web based assembly with native church buildings who may be capable to assist with hire funds, meals, job searches and transportation.

Companies would battle with out the assistance of the church buildings. And church buildings don’t have the sources, coaching or bandwidth to hold out the work of the companies.

However Rykov knew that in the intervening time, he’d want extra assist than ever from church volunteers.

“With out your intervention right here, that is gonna be a humanitarian catastrophe in Nashville,” he instructed them within the on-line assembly held a few week after the cuts. “And in each group, clearly, however we had been specializing in ours. We’re not gonna be ready to assist in the identical manner for much longer, and it is a stark actuality that we’re dealing with.”

Then he went on the native information, warning that “this instant funding freeze places these just lately arrived refugees actually susceptible to homelessness.” The responses on social media mirrored the hate and intolerance that had polluted the nationwide dialog about immigration.

“The frequent theme was, ‘Refugees? Do you imply “unlawful invaders”?’” Rykov recalled. “Persons are so fully misinformed, clearly not studying the article or watching the story, and it’s very disappointing to see that. And I suppose it’s unhappy too that I count on it.”

One Month After the Cuts

“No Time to Screw Round”

In late February, church volunteer Abdul Makembe and a program supervisor from NICE squeezed into the cramped residence of a household of 5 from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Each Makembe and NICE had been working with the household for months, however with the lack of funding, NICE might now not supply help and had requested Makembe to be extra concerned.

Abdul Makembe, who immigrated from Tanzania, volunteers to assist African households settle within the U.S.

Credit score:

Arielle Weenonia Grey for ProPublica

A local of Tanzania, Makembe moved to Tennessee within the late Nineteen Seventies. After working in infectious illness analysis and nonprofit administration, which concerned a number of journeys to Africa, he retired in 2015 and commenced volunteering to assist newly arrived African households. Rykov got here to know him as a fixture of the refugee group, all the time keen to assist.

Within the residence, Makembe perched on the sting of a sofa and Mungaga Akilimali sat throughout from him on the ground.

“So, the scenario has improved a bit of bit?” Makembe requested.

The Congolese man ran his palms over his head.

“The scenario, up to now, not but,” Akilimali stated. “I’m simply making an attempt to use and reapply and reapply, however up to now nothing.”

Akilimali and his household fled the Democratic Republic of Congo greater than 10 years in the past. Since 1996, troopers and militias have killed 6 million folks there and dedicated atrocities in opposition to numerous civilians. Warfare, political instability and widespread poverty have displaced hundreds of thousands of others.

Akilimali and his spouse settled for a time in South Africa, the place they encountered xenophobia and anti-immigrant violence. Immigrants and refugees have turn out to be political scapegoats there, spawning a rash of assaults and even murders. His spouse, Bulonza Chishamara, almost died there in 2018 after an ambush by an anti-immigrant mob.

Docs gave her eight items of blood and Chishamara spent days paralyzed in a hospital mattress, Akilimali stated. She nonetheless walks with a limp.

The household had rejoiced after they obtained accepted for refugee resettlement in 2024 in Tennessee. Their new life in Nashville started with promise. Akilimali, who speaks fluent English and skilled as a mechanic, obtained a driver’s license and a job at Nissan.

Nonetheless, he misplaced the job earlier than his probationary interval ended because of layoffs, and he hasn’t been capable of finding one other one. NICE used to have a strong employees of employment specialists. However the cuts pressured the group to reassign them.

That left fewer sources for folks like Akilimali, who had been within the U.S. longer than the three months throughout which new refugees had been eligible for state division assist however who nonetheless wanted assist discovering work.

For Rykov, the work of spreading consciousness in regards to the cuts and elevating funds to offset them intensified all through February. He and others working with refugees throughout the nation had been hoping that the courts may pressure the administration to launch the federal cash — that if they may hold issues afloat within the brief time period, reduction would come.

Then, on Feb. 25, a federal choose in Washington dominated in favor of the companies. He ordered the administration to revive funds and restart refugee admissions.

The reduction was short-lived. A day later, the administration canceled contracts with resettlement companies, and legal professionals for the administration have appealed the order. Their argument: The gutted refugee companies now not have capability to restart resettlement, making it not possible to adjust to court docket orders.

Rykov stated a number of the diminished variety of remaining employees members started to search for new jobs.

After that, Rykov and his crew kicked into emergency mode. They labored lengthy hours making telephone calls and arranging conferences with potential volunteers and donors.

“It was a cocktail of feelings,” he stated. The generosity of donors and volunteers stuffed him with gratitude. However he couldn’t escape the sense of foreboding that consumed the workplace, the place many desks sat empty and remaining staff voiced deepening issues in regards to the fates of their purchasers.

Rykov likened the pressing vitality at NICE to the aftermath of a pure catastrophe. “There’s no time to screw round.”

On the identical time, staffers apprehensive in regards to the cratering price range and the way forward for the group. And it was arduous to not discover how a lot the temper in Tennessee and across the nation was shifting. In an order suspending refugee admissions, Trump described immigrants as a “burden” who’ve “inundated” American cities and cities.NICE had all the time felt protected, powered by an idealistic and numerous employees who selected to work in refugee resettlement regardless of the lengthy hours and low pay. The cuts and the discourse eroded that sense of security, Rykov stated.

In February, a tech firm supplied him a job in Birmingham. It was an opportunity to be nearer to his mother and father and again within the metropolis the place he’d come of age — a reminder of an period that felt kinder than the present one. He took the job.

“Working at NICE, it’s the very best job I ever had and probably the most significant job I ever had,” he stated.

Rykov packed up just a few issues from NICE. A Ukrainian flag lapel pin. A signed {photograph} of him and his coworkers. In his Birmingham residence, he positioned the image on a bookshelf subsequent to considered one of him and his mother and father at his highschool commencement.

By the point he left, NICE’s refugee resettlement crew was all the way down to 30 staff; it had been 56 earlier than the cuts. For its half, NICE has vowed to hold on. The group has paired 24 households with volunteer mentors for the reason that funding cuts.

Church volunteers, who had been accustomed to serving to furnish and embellish residences for brand spanking new arrivals, now had to assist stop evictions. They needed to observe down paperwork and assist full paperwork misplaced within the confusion of the nonprofit’s layoffs. And the group of largely retired professionals now needed to help with the daunting activity of discovering unskilled jobs for refugees who didn’t converse a lot English.

Two Months After the Cuts

One Volunteer, Many Individuals in Want

On a mid-March morning, Makembe woke at 6 a.m. to start tackling his volunteer work for NICE. Regardless of the lengthy hours he clocks volunteering, the 74-year-old has saved his vitality stage and his spirits up. As he left the storage residence he shares together with his spouse in a tough north Nashville neighborhood, he made certain to double-check the locks.

On today, he was working not with the Akilimali household however with a household of 4 who just lately arrived from Africa. The kid must see a specialist on the Kids’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

It was Vanderbilt that introduced Makembe to Nashville many years in the past, for his grasp’s diploma in financial planning. He adopted that with a doctorate in well being coverage and analysis on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Over time that adopted, he made repeated journeys again to Tanzania to do analysis on malaria and parasitic infections.

All that took a toll on Makembe’s marriage, and he and his first spouse divorced when his two youngsters had been very younger. They’re now grown and profitable. His son is an accountant and his daughter just lately completed legislation faculty and works at a agency in New York. That leaves him extra time to spend with refugees.

However the volunteer work does deliver some monetary stress. He’s making an attempt to save lots of $5,000 to use for a inexperienced card for his spouse, which is hard. As a result of he spent a lot of his profession working outdoors the U.S., Makembe receives lower than $1,000 a month from Social Safety. He drives a 2004 Toyota that was donated to his church to assist the congregation’s work with refugees, however he pays out of pocket for gasoline and automobile insurance coverage. The prices can add up. It’s not unusual for him to burn 1 / 4 tank of gasoline a day when he’s volunteering.

Makembe’s church, Woodmont Hills Church, is a big contributor to the town’s refugee resettlement work — an ethos shared by its present congregants however that has led to the lack of members through the years. Although it had a congregation nearing 3,000 members within the late ’90s, attendance shrank because the church’s ideology grew extra progressive and Tennessee’s grew extra conservative. It’s now all the way down to 800 members.

But the church remained steadfast in its dedication to serving to refugees. Its leaders invited NICE to carry courses in its empty assembly rooms and made house to deal with a Swahili church and a Baptist church shaped by refugees from Myanmar. And when NICE misplaced funding, Woodmont Hills members donated their money and time.

Makembe has helped dozens of refugees through the years however was significantly apprehensive for the household he needed to take to the Kids’s Hospital that March morning, serving as each driver and translator. They arrived proper earlier than Trump lower off funding, they usually had struggled to get medical care for his or her 5-year-old’s persistent seizures. A physician at a neighborhood clinic had prescribed antiseizure remedy, nevertheless it didn’t work, and the kid skilled episodes the place his muscle groups tensed and froze for minutes at a time.

Nashville has world-class medical services, however NICE now not had employees obtainable to assist the household perceive and navigate that care, leaving them pissed off.

It took months for the household to get in to see a specialist. Through the lengthy wait, Makembe stated, the boy’s father started to lose hope. His son’s seizures had turn out to be longer and extra frequent. Makembe stepped in to assist them get a referral from a physician on the native clinic.

The kid’s father needed to miss the physician’s appointment that March morning in order that he might go to an interview at an organization that packages pc components. Each he and his spouse had been trying to find jobs and putting out. Makembe has tried to assist however has run into limitations. He doesn’t have the identical connections with labor companies that NICE staffers did.

Trump’s DOJ Has Frozen Police Reform Work. Advocates Worry Extra Abuse in Departments Throughout the Nation.

Makembe stated he needs to get the kid enrolled in a particular faculty for the autumn and discover a wheelchair so his mother received’t have to hold him.

And that’s simply this household. Makembe stated new refugees have been ready for months to get job interviews. When he visits the 5 households he mentors, their neighbors method him asking for assist. A lot of their requests are for the help NICE and different refugee companies as soon as supplied.

“I’m very a lot apprehensive,” he stated. “I imply, they do not know of what to do.”