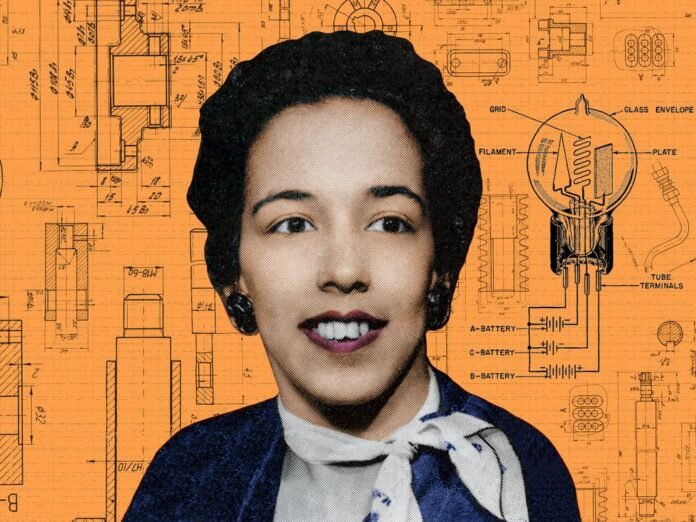

For greater than a century, girls and racial minorities have fought for entry to training and employment alternatives as soon as reserved solely for white males. The lifetime of Yvonne Younger “Y.Y.” Clark is a testomony to the facility of perseverance in that combat. As a sensible Black lady who shattered the boundaries imposed by race and gender, she made historical past a number of occasions throughout her profession in academia and trade.

She in all probability is finest generally known as the primary lady to function a school member intheengineering school at Tennessee State Collegein Nashville. Her pioneering spirit prolonged far past the classroom, nevertheless, as she repeatedly staked out new territory for girls and Black professionals in engineering. She achieved loads earlier than she died on 27 January 2019 at her house in Nashville on the age of 89.

Clark is the topic of the most recent biography in IEEE-USA’s Well-known Girls Engineers in Historical past collection. “Don’t Give Up” was her mantra.

An early ardour for know-how

Born on 13 April 1929 in Houston, Clark moved along with her household to Louisville,Ky., as a child. She was raised in an academically pushed family. Her father, Dr. Coleman M. Younger Jr., was a surgeon. Her mom, Hortense H. Younger, was a library scientist and journalist. Her mom’s “Tense Matters” column, printed by the Louisville Defender newspaper, tackled segregation, housing discrimination, and civil rights points, instilling consciousness of social justice in Y.Y.

Clark’s ardour for know-how turned evident at a younger age. As a baby, she secretly repaired her household’s malfunctioning toaster, stunning her mother and father. It was a defining second, signaling to her household that she was destined for a profession in engineering—not in training like her older sister, a highschool math instructor.

“Y.Y.’s household didn’t create her ardour or her skills. These had been her personal,” mentioned Carol Sutton Lewis, co-host and producer for the third season of the “Misplaced Girls of Science” podcaston which Clark was profiled. “What her household did do, and what they might proceed to do, was make her pursuits viable in a world that wasn’t truthful.”

Clark’s curiosity in finding out engineering was precipitated by her ardour for aeronautics. She mentioned all of the pilots she spoke with had studied engineering, so she was decided to take action. She joined the Civil Air Patrol and took simulated flying classes. She then realized to fly an airplane with the assistance of a household buddy.

Regardless of her educational excellence, although, racial boundaries stood in her manner. She graduated at age 16 from Louisville’s Central Excessive Collegein 1945. Her mother and father, involved that she was too younger to attend school, despatched her to Boston for 2 extra years on the Women’ Latin College and Roxbury Memorial Excessive College.

She then utilized to the College of Louisvillethe place she was initially accepted and supplied a full scholarship. When college directors realized she was Black, nevertheless, they rescinded the scholarship and the admission, Clark mentioned on the “Misplaced Girls of Science” podcast, which included clips from when her daughter interviewed her in 2007. As Clark defined within the interview, the state of Kentucky supplied to pay her tuition to attend Howard Collegea traditionally Black school in Washington, D.C., reasonably than combine its publicly funded college.

Breaking boundaries in increased training

Though Howard offered a chance, it was not freed from discrimination. Clark confronted gender-based boundaries, in response to the IEEE-USA biography. She was the one lady amongst 300 mechanical engineeringstudents, a lot of whom had been World Conflict II veterans.

“Y.Y.’s household didn’t create her ardour or her skills. These had been her personal. What her household did do, and what they might proceed to do, was make her pursuits viable in a world that wasn’t truthful.” —Carol Sutton Lewis

Regardless of the challenges, she persevered and in 1951 turned the primary lady to earn a bachelor’s diploma in mechanical engineering from the college. The college downplayed her historic achievement, nevertheless. The truth is, she was not allowed to march along with her classmates at commencement. As a substitute, she acquired her diploma throughout a non-public ceremony within the college president’s workplace.

A profession outlined by firsts

Decided to forge a profession in engineering, Clark repeatedly encountered racial and gender discrimination. In a 2007 Society of Girls Engineers (SWE) StoryCorps interviewshe recalled that when she utilized for an engineering place with the U.S. Navythe interviewer bluntly informed her, “I don’t suppose I can rent you.” When she requested why not, he replied, “You’re feminine, and all engineers exit on a shakedown cruise,” the journey throughout which the efficiency of a ship is examined earlier than it enters service or after it undergoes main modifications equivalent to an overhaul. She mentioned the interviewer informed her, “The omen is: ‘No females on the shakedown cruise.’”

Clark finally landed a job with the U.S. Military’s Frankford Arsenal gauge laboratories in Philadelphia, changing into the primary Black lady employed there. She designed gauges and finalized product drawings for the small-arms ammunition and range-finding devices manufactured there. Tensions arose, nevertheless, when a few of her colleagues resented that she earned more cash because of extra time pay, in response to the IEEE-USA biography. To ease office tensions, the Military lowered her hours, prompting her to hunt different alternatives.

Her future husband, Invoice Clark, noticed the issue she was having securing interviews, and prompt she use the gender-neutral title Y.Y. on her résumé.

The tactic labored. She turned the primary Black lady employed by RCA in 1955. She labored for the corporate’s digital tube division in Camden, N.J.

Though she excelled at designing manufacturing unit tools, she encountered extra office hostility.

“Sadly,” the IEEE-USA biography says, she “felt animosity from her colleagues and resentment for her success.”

When Invoice, who had taken a school place as a biochemistry teacher at Meharry Medical School in Nashville, proposed marriage, she eagerly accepted. They married in December 1955, and he or she moved to Nashville.

In 1956 Clark utilized for a full-time place at Ford Motor Co.’sNashville glass plant, the place she had interned through the summers whereas she was a Howard pupil. Regardless of her {qualifications}, she was denied the job because of her race and gender, she mentioned.

She determined to pursue a profession in academia, changing into in 1956 the primary lady to show mechanical engineering at Tennessee State College. In 1965 she turned the primary lady to chairTSU’smechanical engineering division.

Whereas educating at TSU, she pursued additional training, incomes a grasp’s diploma in engineering administration from Nashville’s Vanderbilt Collegein 1972—one other step in her lifelong dedication to skilled progress.

After 55 years with the college, the place she was additionally a freshman pupil advisor for a lot of that point, Clark retired in 2011 and was named professor emeritus.

A legacy of management and advocacy

Clark’s affect prolonged far past TSU. She was energetic within the Society of Girls Engineers after changing into its first Black member in 1951.

Racism, nevertheless, adopted her even inside skilled circles.

On the 1957 SWE convention in Houston, the occasion’s lodge initially refused her entry because of segregation insurance policies, in response to a 2022 profile of Clark. Beneath strain from the society’s management, the lodge compromised; Clark may attend periods however needed to be escorted by a white lady always and was not allowed to remain within the lodge regardless of having paid for a room. She was reimbursed and as a substitute stayed with family.

Because of that incident, the SWE vowed by no means once more to carry a convention in a segregated metropolis.

Over the many years, Clark remained a champion for girls in STEM. In a single SWE interview, she suggested future generations: “Put together your self. Do your work. Don’t be afraid to ask questions, and profit by assembly with different girls. No matter you want, find out about it and pursue it.

“The surroundings is what you make it. Typically the surroundings is hostile, however don’t fear about it. Pay attention to it so that you aren’t blindsided.”

Her contributions earned her quite a few accolades together with the 1998 SWE Distinguished Engineering Educator Award and the 2001 Tennessee Society of Skilled Engineers Distinguished Service Award.

An enduring impression

Clark’s legacy was not confined to engineering; she was deeply concerned in Nashville neighborhood service. She served on the board of the 18th Avenue Household Enrichment Heart and took part within the Nashville Space Chamber of Commerce. She was energetic within the Hendersonville Space chapter of The Hyperlinks, a volunteer service group for Black girls, and the Nashville alumnae chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority. She additionally mentored members of the Boy Scoutsa lot of whom went on to pursue engineering careers.

Clark spent her life pulling down boundaries that attempted to impede her. She didn’t simply break the glass ceiling—she engineered a manner by it for individuals who got here after her.

From Your Website Articles

Associated Articles Across the Net